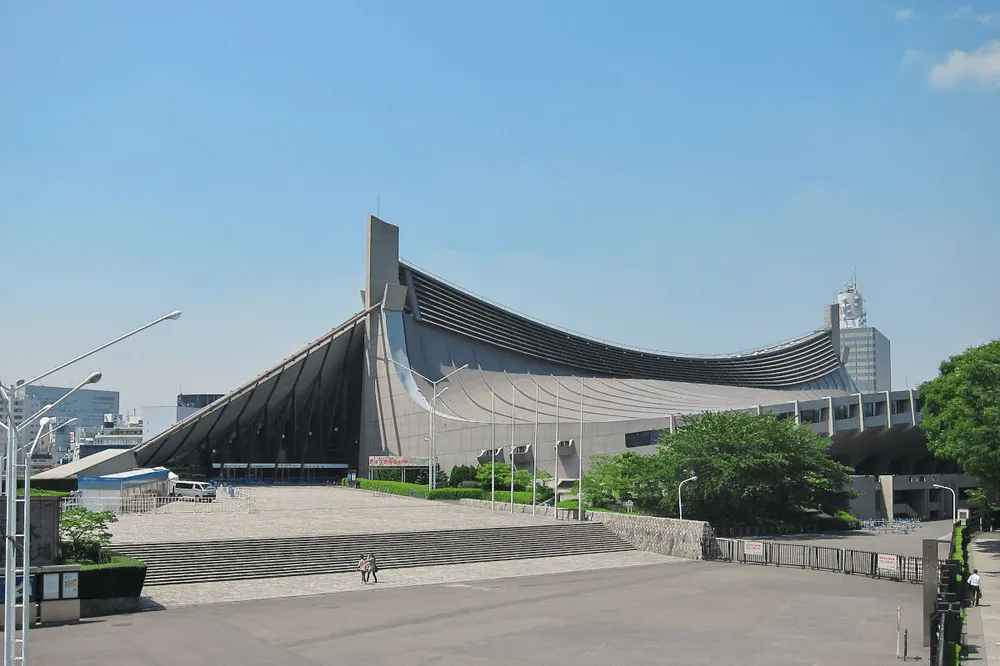

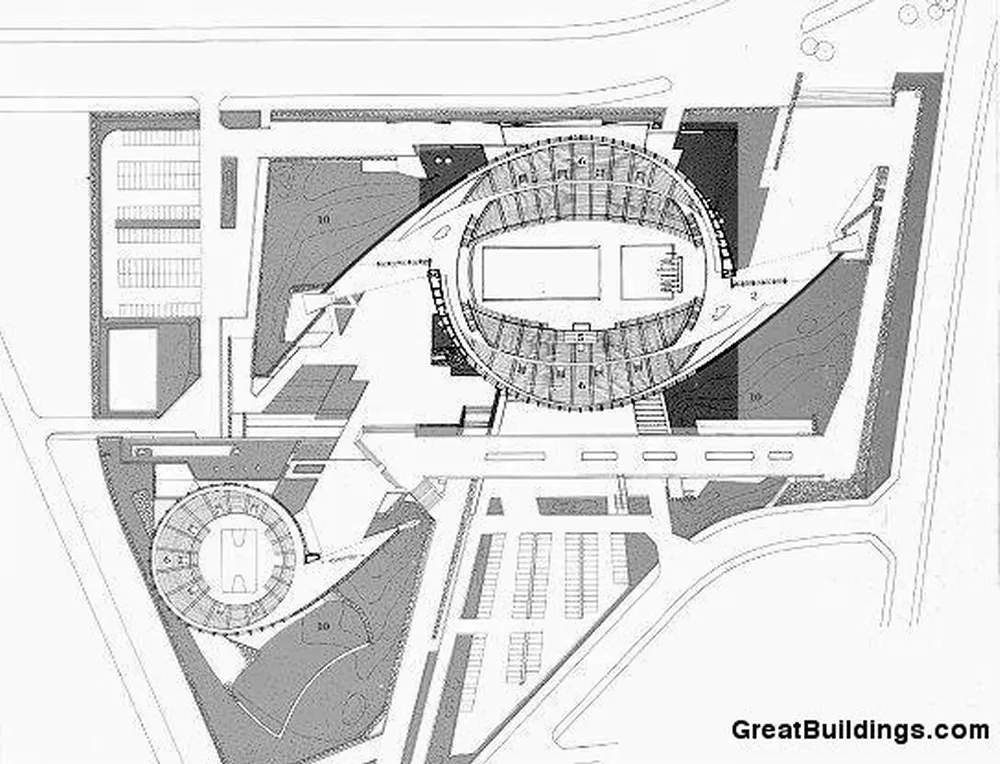

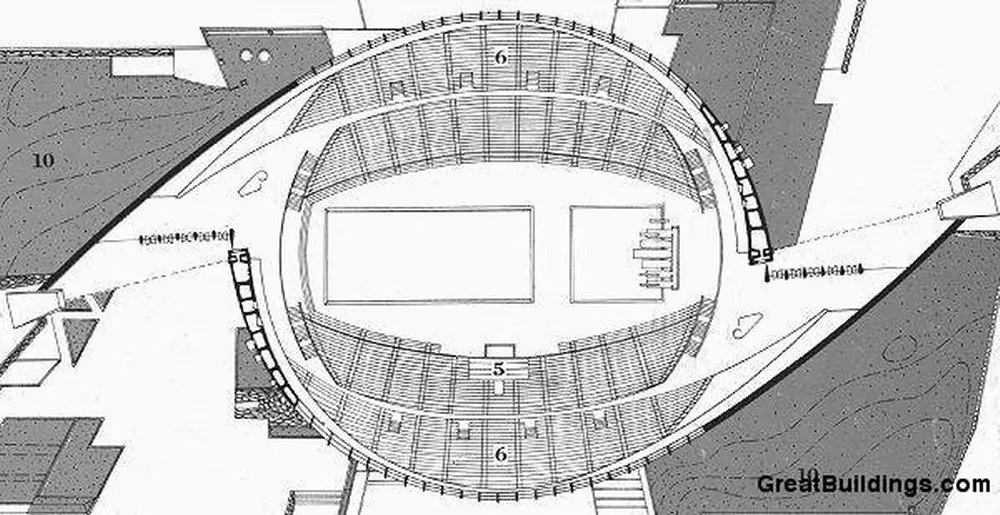

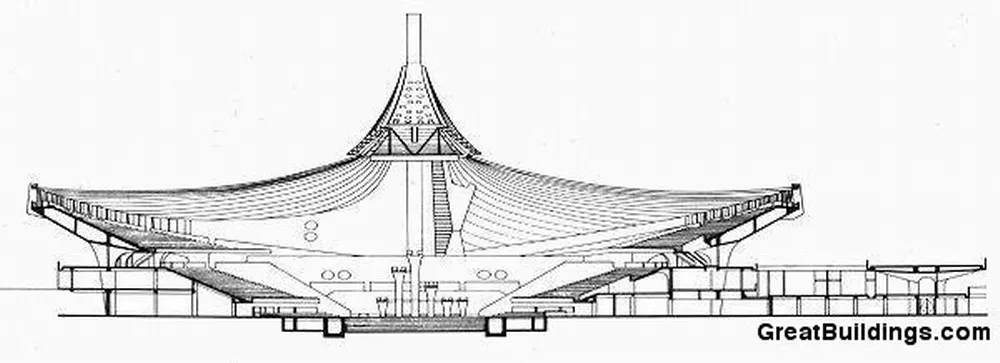

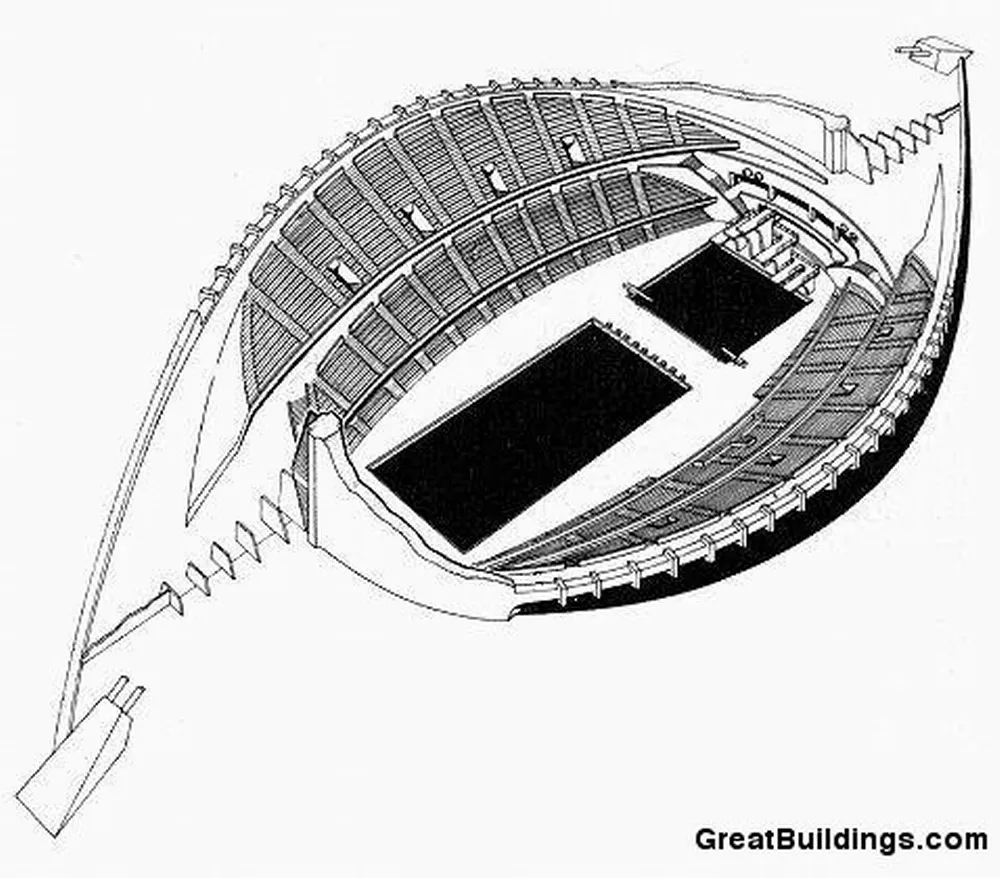

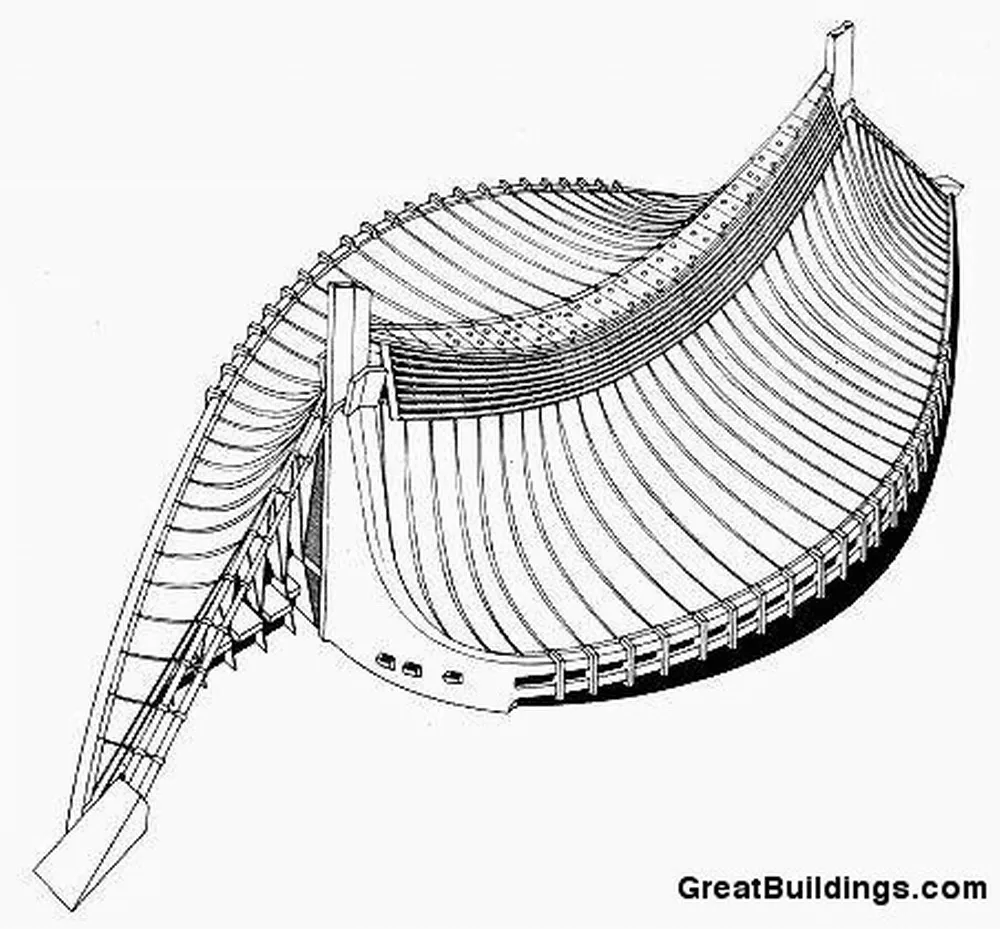

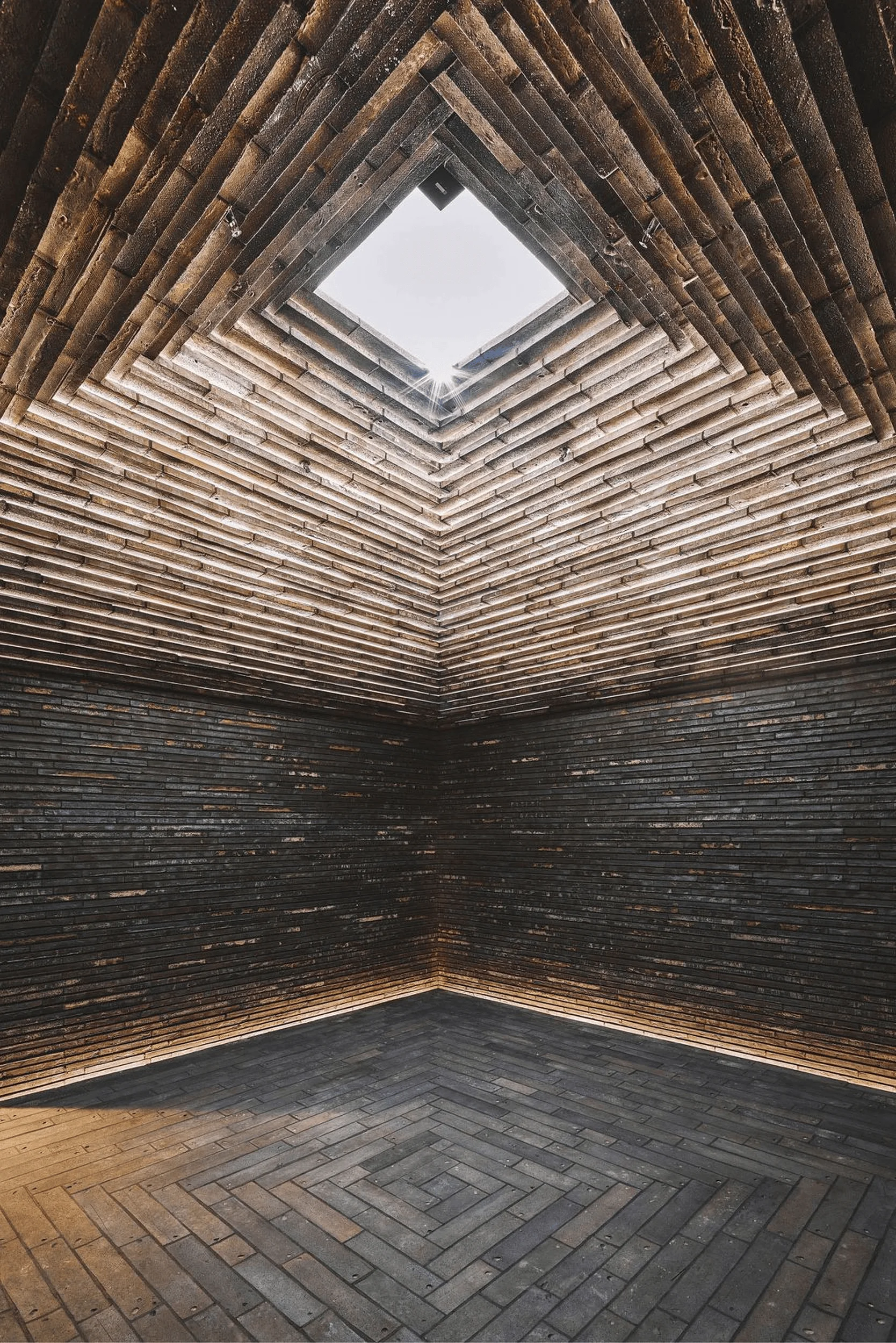

The Yoyogi National Gymnasium, built for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan, stands as an architectural landmark due to its distinctive design. Designed by one of Japan’s most prominent modernists, Kenzo Tange, the gymnasium blends Western modernist aesthetics with traditional Japanese architecture. Tange’s innovative structural design creates dramatic curves that seem to effortlessly hang from two large central supporting cables. Its dynamic suspended roof and rough materials have come to embody one of the world’s most iconic architectural silhouettes. Nestled within one of Tokyo’s largest urban parks, Tange used the environment as a way to integrate his architecture into the landscape. The subtle curves of the structural cables, the sweeping roof plane, and the curved concrete base seem to emerge from the site, appearing as a single whole. The gymnasium was the larger of two venues designed by Tange for the 1964 Summer Olympics, both employing similar structural principles and aesthetics. The smaller pavilion, with a capacity of around 5,300, was used for various smaller Olympic events, while the National Gymnasium was designed to hold 10,500, mainly for the Olympic swimming and diving competitions. However, it could be converted into a space to accommodate larger events such as basketball and ice hockey. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s Philip’s Pavilion and Eero Saarinen’s Yale University Hockey Rink, Tange developed an interest in structures and their tensile and geometrical potential. Similar to Saarinen’s design for Yale’s hockey rink, Tange implemented a central structural spine from which the structure and roof originated. In addition to being anchored to concrete supports on the ground, two large steel cables are suspended between two structural towers. The cables form a tensioned tent-like roof structure; a series of prestressed cables hang from the two main cables that are suspended from the concrete structure that forms the bottom of the gymnasium and provides the necessary structure for the seating within the stadium. The result is a symmetrical suspended structure that gracefully hangs from the central structural spine. Its flowing surfaces make the minimal surface structure appear to be a fabric hanging from two simple supports, pulled into tension by the landscape. Merging Japanese architectural aesthetics with Western modernist design, the gymnasium’s structural system is similar to a snail’s shell, but in a more contextual sense, the gymnasium’s low profile and sweeping roof forms an abstract Japanese pagoda-like appearance. When the Yoyogi National Gymnasium was built, it had the largest free-span roof in the world. Its dynamic form and structural expressionism make the gymnasium one of Kenzo Tange’s most important works and a progressive architectural landmark. Today, it remains one of Tokyo’s most sought-after tourist destinations while continuing to be a venue for international sports and fashion events. “We Japanese architects, in our efforts to solve the problems facing modern Japan, have paid great attention to Japanese tradition, ultimately reaching the point I’m trying to elucidate for you. If, however, in my works, or those of my generation, one can detect a whiff of tradition, then our creativity has not yet reached its prime, then we are still in the throes of development in our creativity. I think, in any case, my architecture is free of the “traditional” label. – Kenzo Tang.

Project Information: