**Origin: Thinking sparked by uncertainty**

In recent years, the topic of rural architecture has become a hot topic in China’s architectural design community, driven by government policy and capital investment. I have always believed that the relationship between place and people is crucial. If one cannot accurately define the life, behavior, and movement of people in a place, early-stage research on uncertainty will generate multiple spatial forms, passively forming a part of polysemic space in the final scheme. Uncertainty is ubiquitous in urban design, and the entire design process, even after completion, needs to address functional changes. To a large extent, this is caused by changes in external conditions such as capital, market, policy, and business models. Like most urban projects, typical rural construction projects cannot escape the “uncertainty” brought by external conditions.

With these thoughts in mind, Space Architecture completed an “atypical” rural residential project in 2019. The owner is a local couple in their sixties. Their house was built over 30 years ago and was classified as a dangerous building by the government a few years ago. The owners decided to rebuild a new home on the original site, as a retirement home for the couple and for their children who live in the city to visit occasionally. Because the owners had absolutely no commercial considerations, the value of the design is fully reflected in the user experience. After communicating with the owners, we decided to design an anti-utopian home for them, immersed in daily life.

**Overall strategy: Responding to the “two sets of rules” of the countryside**

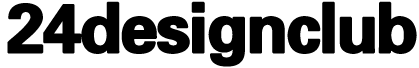

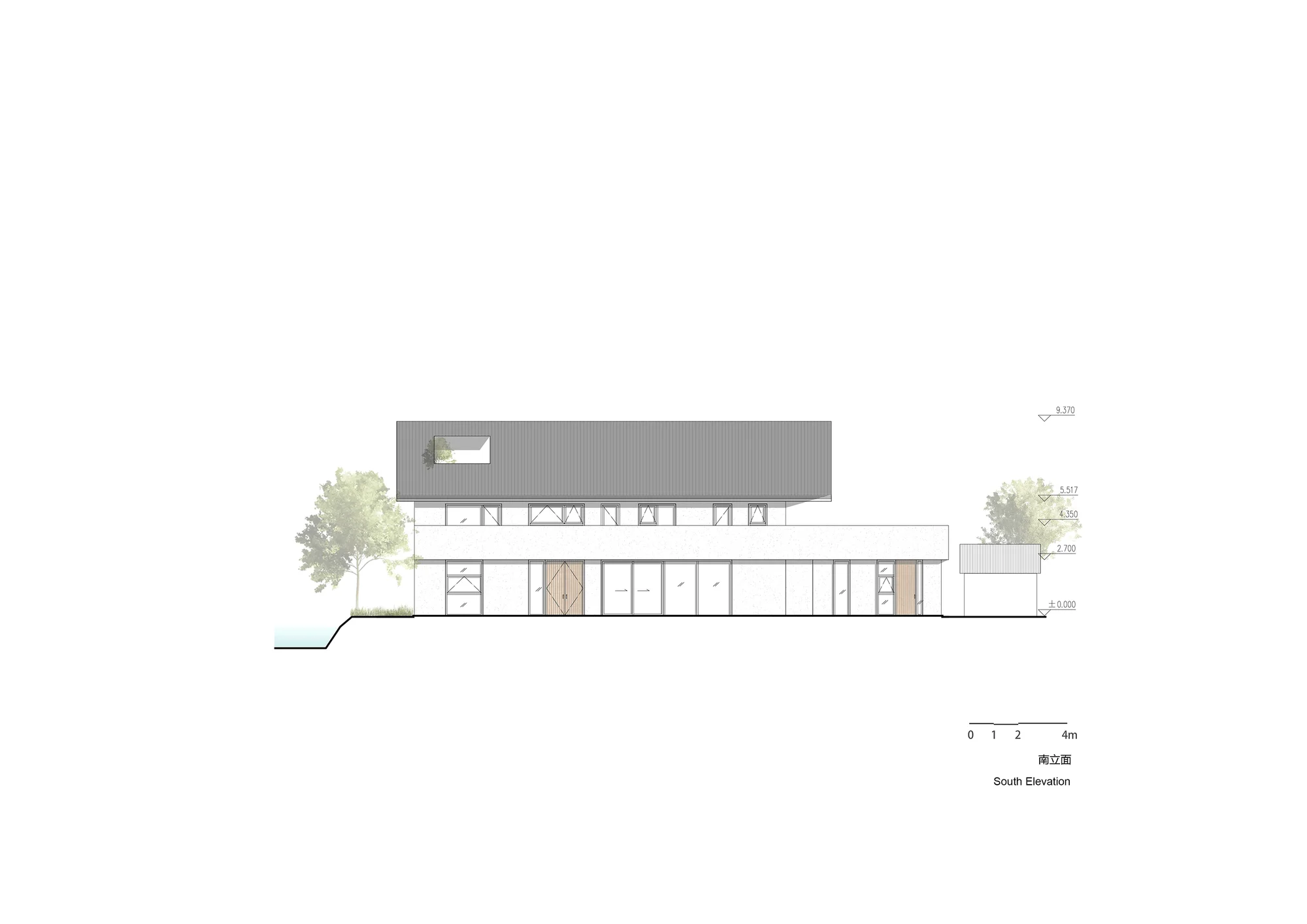

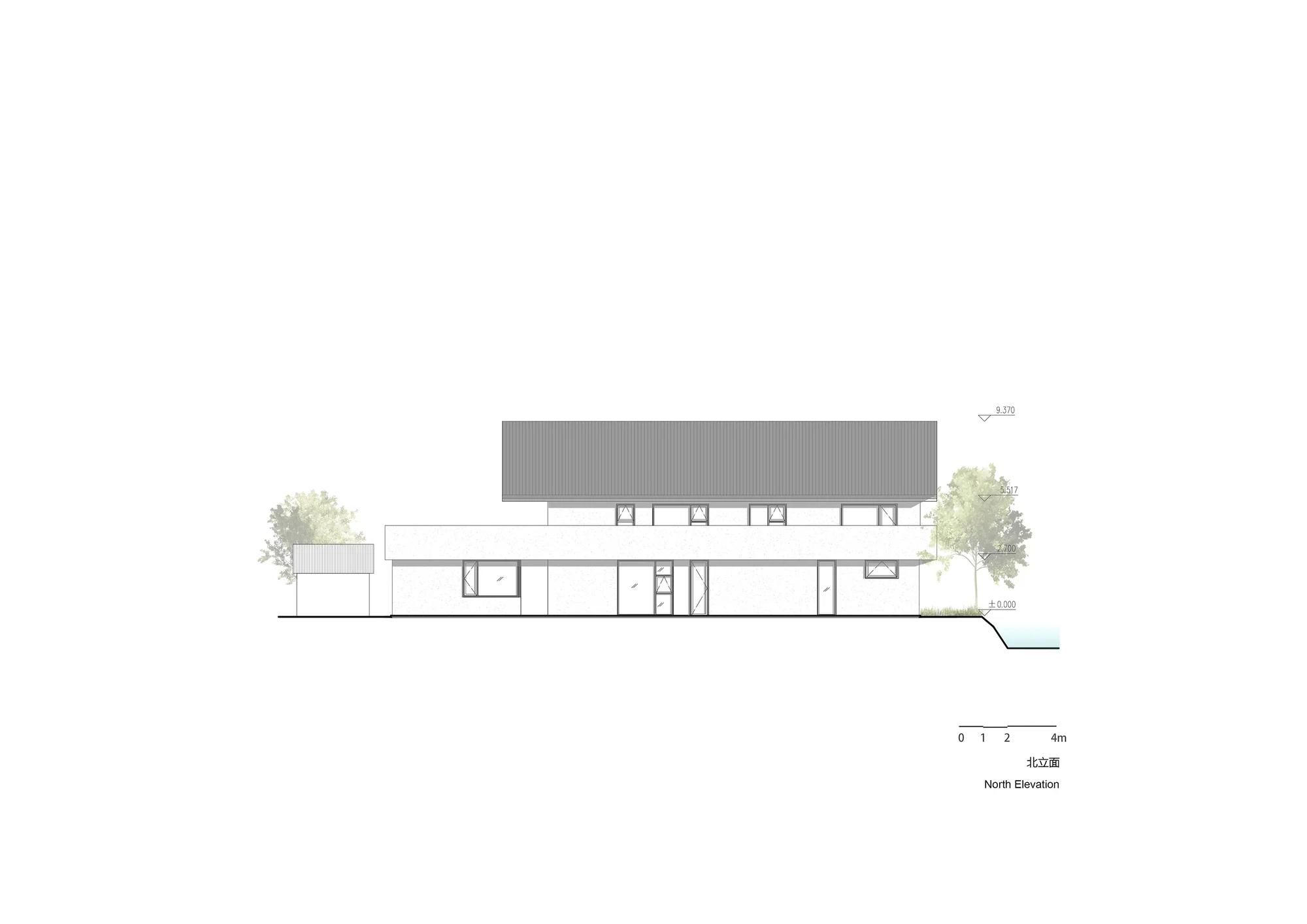

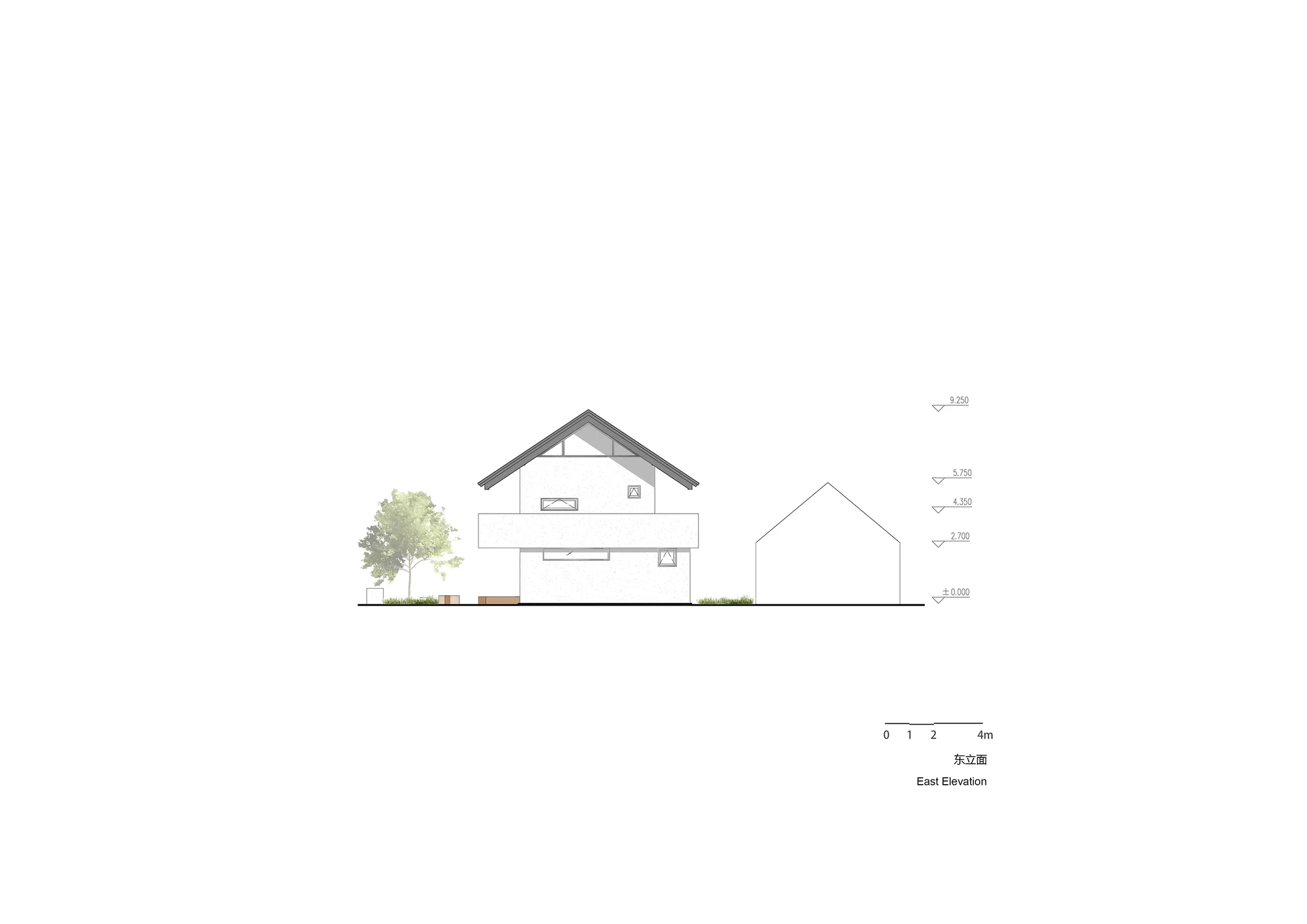

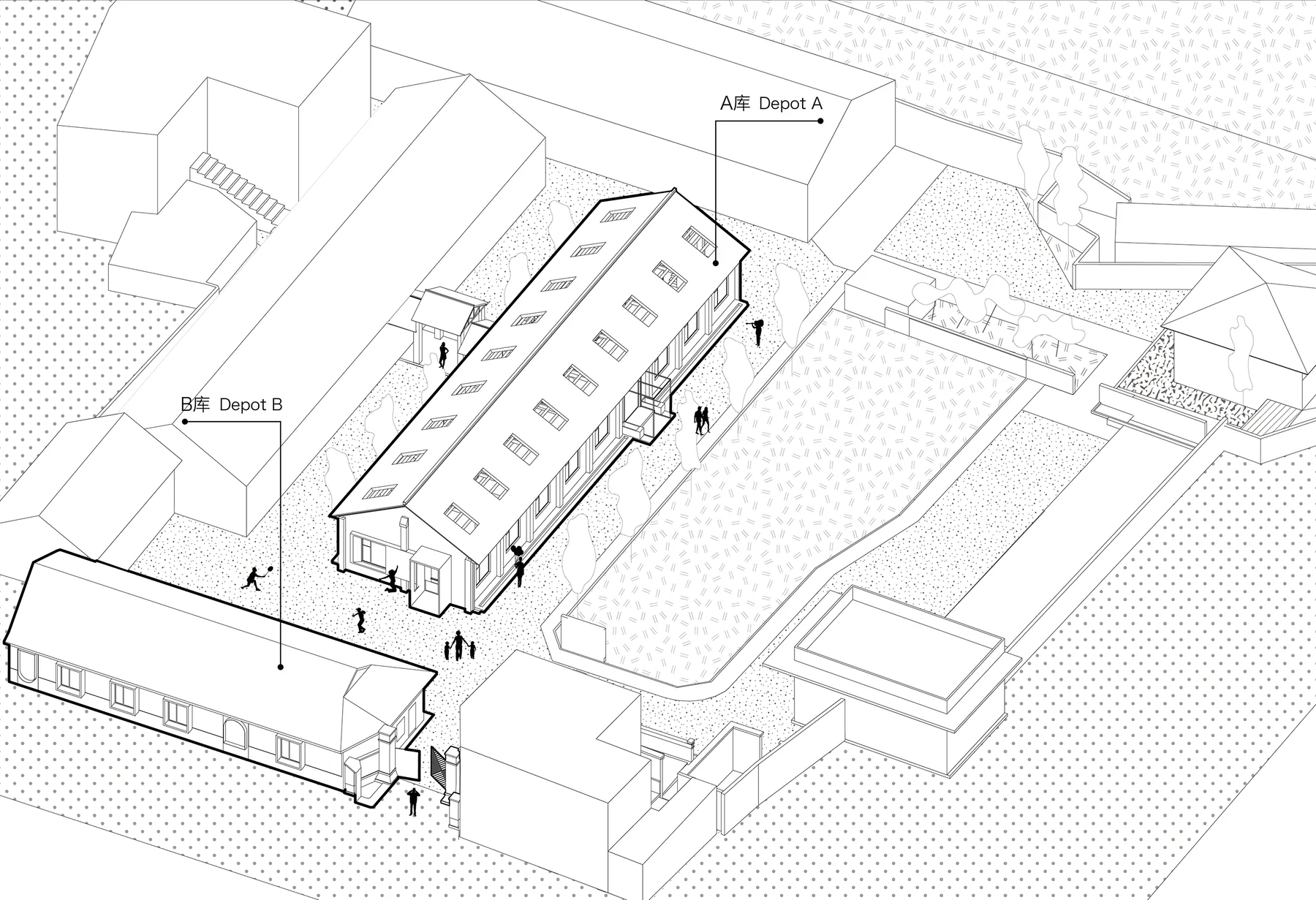

The project is located in the suburbs of Shanghai, with other village houses to the east and west, open farmland to the south, and a road to the north. The original house and most of the self-built houses in the village are similar in form, with the main house being two stories high and the auxiliary building sharing a gable wall with the main house, with only one story. Both the main and auxiliary buildings have gable roofs. Before conducting in-depth research, we believed that the reason why rural self-built houses in the Jiangzhe region are so monotonous is that the owners do not value design enough. Under the constraints of limited construction costs and construction techniques, they can only adopt the same form to obtain more rooms and area, and aesthetic pursuits are not even discussed. In fact, the design requirements of self-built houses are a systematic decision-making process, and the impact of design specifications on the scheme even exceeds the cost, technology, and aesthetics.

The design of rural private houses needs to face the restrictions of two sets of rules: first, rural self-built house management regulations, such as the roof ridge and eaves height must be unified, and data such as residential area and plot area are also explicitly limited; second, the “rules” that are customary in the area, such as balconies and terraces are not included in the house area, the gable walls of houses facing the road on the north and south sides must be aligned, the south facade of the house cannot be further south than the north facade of the house next door to the west, and arched windows cannot be made on the gable wall, etc. The two sets of rules, design specifications, and local rules, work together to generate the texture of modern villages, clearly defining the overall dimensions and form of the building.

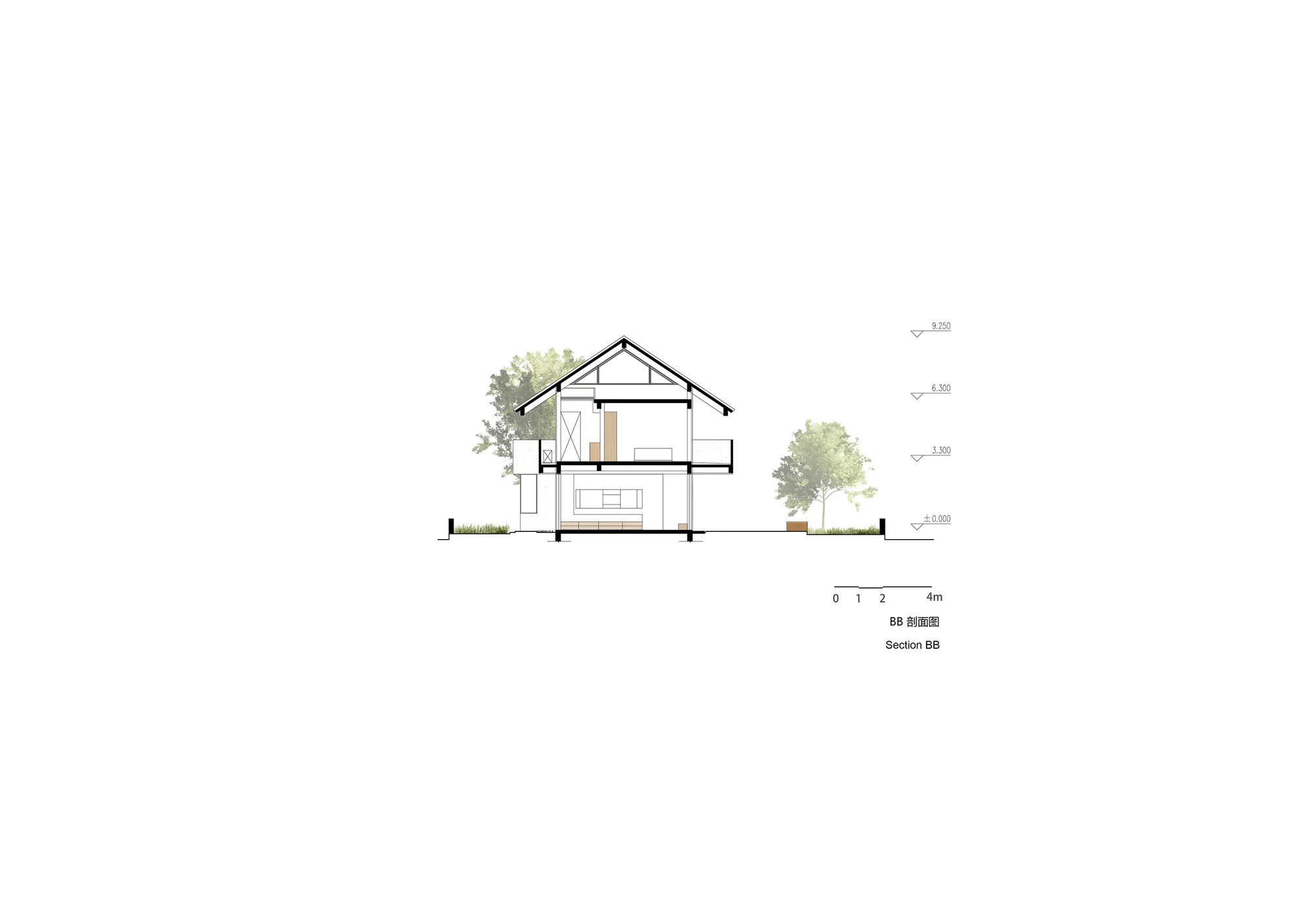

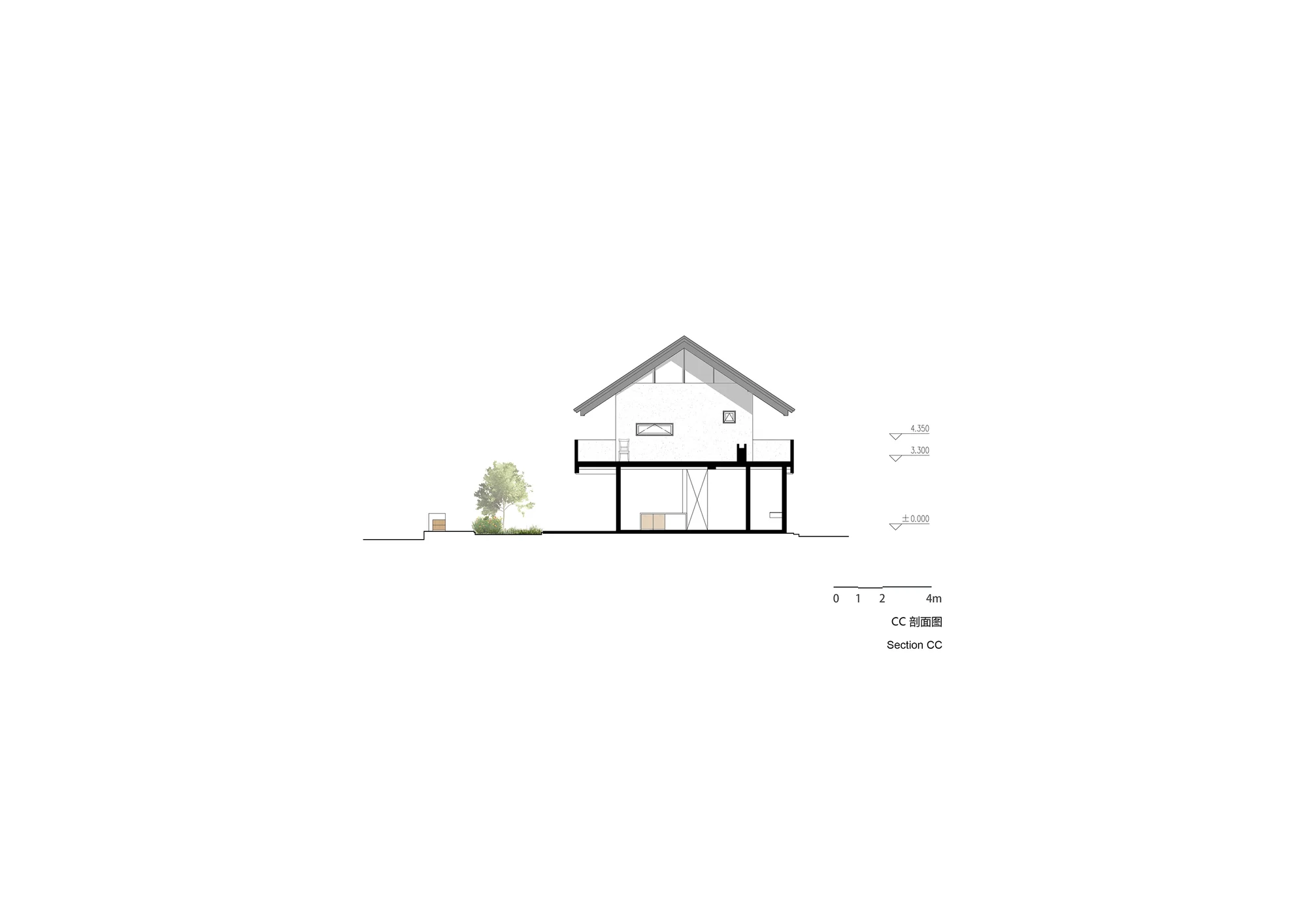

We decided to adopt a low-key posture to actively integrate into the local rural texture. Through analysis of the two sets of rules and in-depth local research, the design naturally presents itself as a north-south gable roof, two-story rectangular volume. While maintaining the area within the regulations, the width is extended, and the south-facing landscape and lighting surface are correspondingly increased. In the part of the house close to the field on the south side, the outdoor vegetable garden and drying yard are preserved, and the architectural design reinforces the language of the eaves of Jiangnan architecture and combines it with gentle horizontal lines, using a pleasant scale to unify the landscape and the building.

**Spatial logic: Public/Shared/Private**

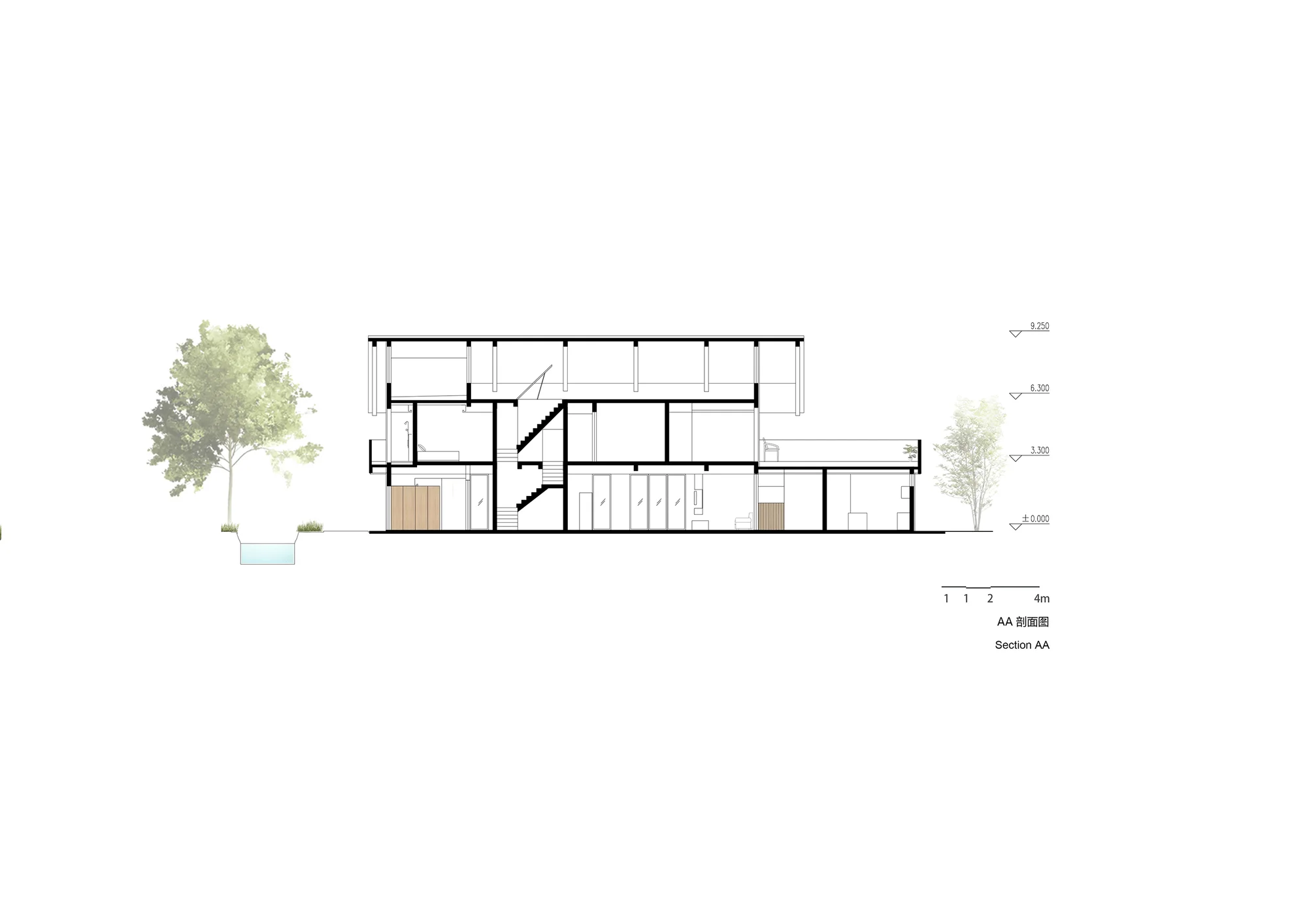

In French, public means a space created by the ruler, while shared means a space created by people themselves. In terms of spatial arrangement, we emphasize the high degree of mutual access between the indoor spaces and the outdoor landscape, integrating and distinguishing the three parts of the building: public/shared/private. For the arrangement of the indoor spaces, meeting the daily life needs of the owner and their neighborly interactions becomes the key to organizing the two-story space.

The vegetable garden in the courtyard on the south side of the first floor is preserved according to the owner’s habits, and a wide washing trough is redesigned on one side. Washing vegetables and dishes, watering the garden, and other tasks are done outdoors on a daily basis. The architect has designed some simple volumes at the boundary of the courtyard to define the site, and when there is no need to dry crops and bedding, this area can also become a place for neighbors to gather and relax. The proportion of mobile population in the village is much lower than in the city, and the relationship between people is closer. We designed a series of shared spaces for the owner and their neighbors, such as a living room, kitchen, and dining room. The concept of the living room is magnified here, and the vegetable garden, drying yard, kitchen, and dining room on the first floor can all be places for neighbors to gather and chat. Pulling out a radish with dirt from the vegetable garden in the courtyard, washing it clean by the vegetable garden, neighbors passing by greet each other at the gate of the courtyard, then move a stool and sit down to chat. When the weather is good, familiar neighbors gather together in the courtyard to wash and clean, kill chickens and fish by the large water tank in the courtyard, and chat about daily life. When cooking, visiting neighbors and the owner stay in the kitchen at the same time, occasionally going down to the vegetable garden to get fresh vegetables.

The rural houses in the Jiangzhe region still retain the layout logic of traditional dwellings – the central space of the main hall or the hall is a sacred space, which needs to undertake the functions of ancestor worship and banquets during major festivals, and other rooms are arranged around this spiritual space. The hall is both the center of family life and the node connecting the interior and exterior. In this design, the concept of the hall overlaps with the living room, forming a transformable space. Almost the entire first floor of the rural house can be shared with neighbors. We hope to fully restore the characteristics of the integration of the interior and exterior of Jiangnan architecture in the node space of the design, so in addition to the kitchen and dining room, auxiliary buildings, the main building’s entrance hall and living room junction is designed with sliding doors, and the entrance hall can also serve as a separate space for playing mahjong or receiving guests.

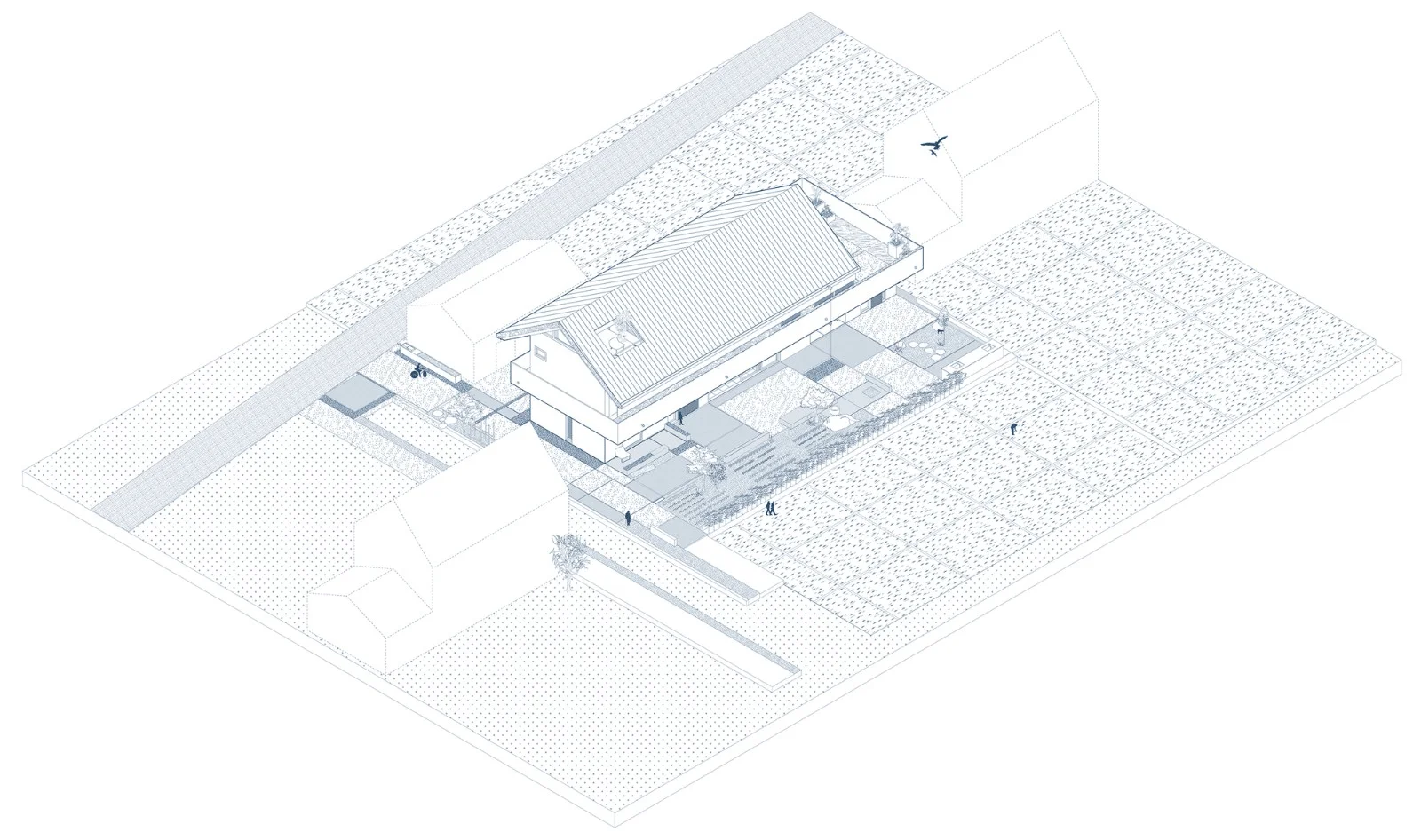

At the stairs, a semi-transparent wooden grille door is designed as a prompt for entering the second floor, and it also separates the shared space from the private space.

**Detail implementation: Two generations of life**

The second floor mainly includes bedrooms for the owners and their children, as well as a corner for occasional family interaction and leisure. The spatial arrangement on the second floor is based on functionality and efficiency, using the corridor to connect the various bedrooms and bathrooms. We designed a simple water bar at the open space in the corridor, extending the concept of “shared” from the entrance hall on the first floor to the second floor, and also resolving the corridor’s function as a pure circulation space. The owner’s children work and live in Shanghai, and they hope to retain the leisure of rural life and the privacy of the city when they return to their parents’ home in the far suburbs. We integrated the guest bedroom and guest bathroom into one complete space, fully considering the needs of vision and lighting in terms of landscape and lighting. Except for the toilet, all the functions of the bathroom are open, and the interior and furniture emphasize the warmth and relaxation brought by the natural wood. We hope that the younger generation who are accustomed to modern life can fully enjoy the freedom of returning to the fields, feeling the imprint of time in nature.

The balcony and terrace on the second floor are extensions of the indoor spaces on the second floor outwards, and occasionally can invite friends to have a relatively private outdoor dinner, barbecue party, and will not be disturbed. The outdoor space on the second floor is closely connected to the first floor and the distant field in terms of vision, but it also retains some distance.

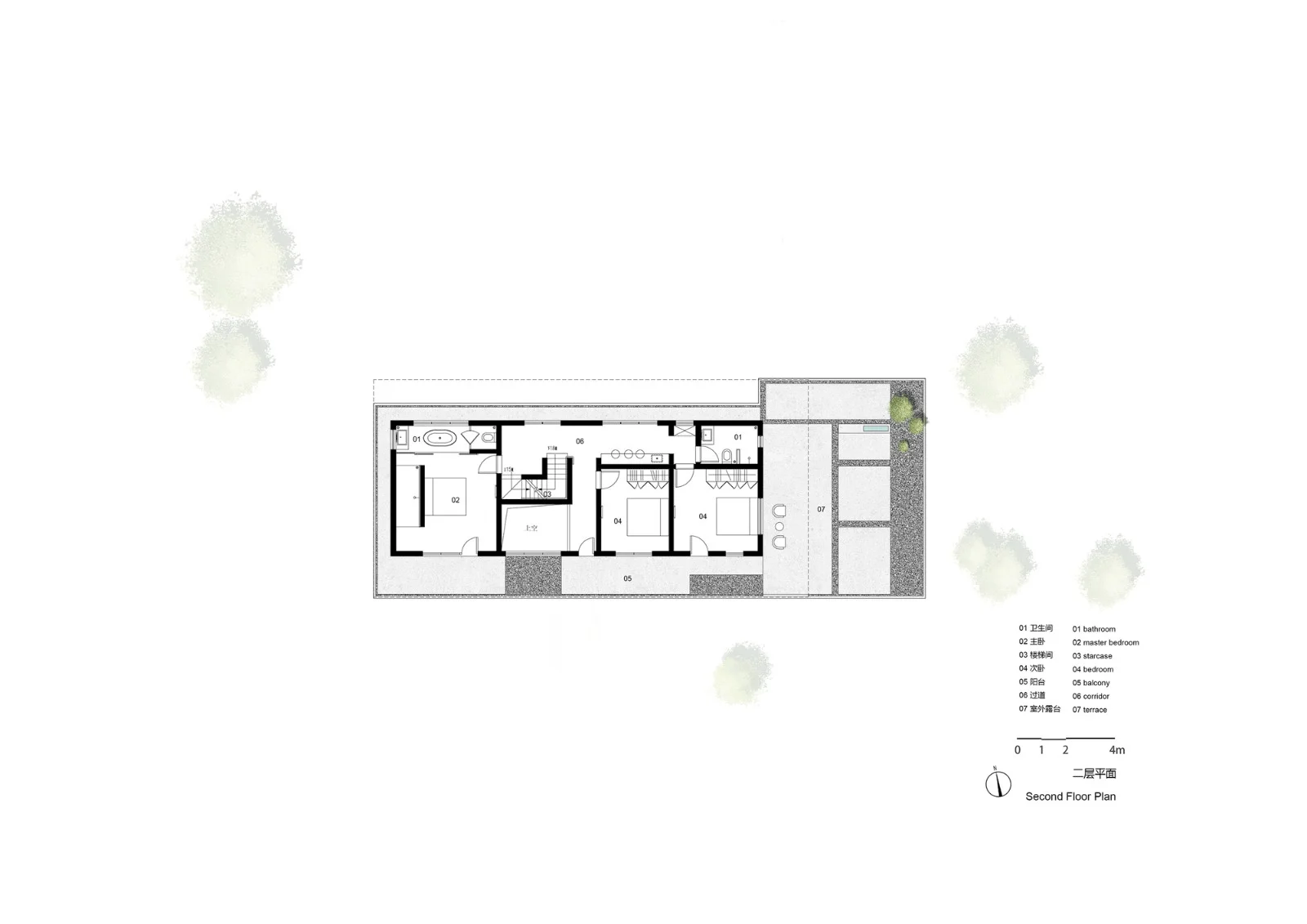

The attic is the most private part of the residence, a complete private space consisting of a multi-functional activity room, a storage room, and a small rooftop outdoor garden. The small garden is located in the highest gable part of the sloped roof, with a hole opened in the sloped roof, resolving the height restriction. In addition to enhancing the lighting and ventilation of the attic, the private attic garden can provide a private space for the daughter who occasionally comes back to stay for a while, a space for contemplation, reflection, and meditation.

**Why build: Possession and use**

Capital is still driving the commercialization of architecture, and the image of the rural lifestyle that people yearn for has given rural construction projects high investment value. Architecture, as a visual cultural symbol, is consumed and disseminated. I believe that the essence of dwelling is the collection of the user’s physical experience in space. When the user enters an image, their spatial experience cannot become dwelling. From this perspective, material construction, form, composition, details, etc., which fall into the discussion of design language, should be attributed to the categories of technology and aesthetics, rather than the ontology of architecture.

As an architect, I often reflect on the question of “why build”. In “architecture as an object of possession” and “architecture as an object of use”, the responsibilities and freedom enjoyed by architects are not the same, and the “uncertainty” in it is always present. These uncertainties can eventually manifest as a radical architectural experiment, or, a review and adventure of life.

Project Information: